How Flu Viruses Gain The Ability To Spread

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

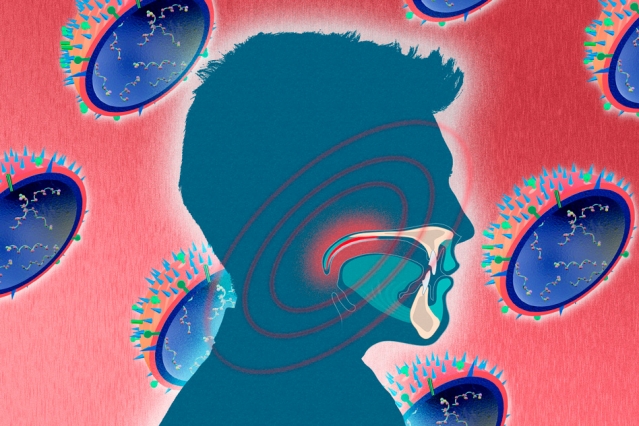

Flu viruses come in many strains, and some are better equipped than others to spread from person to person. Scientists have now discovered that the soft palate — the soft tissue at the back of the roof of the mouth — plays a key role in viruses’ ability to travel through the air from one person to another.

The findings should help scientists better understand how the flu virus evolves airborne transmissibility and assist them in monitoring the emergence of strains with potential to cause global outbreaks.

Researchers from MIT and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) made the surprising finding while examining the H1N1 flu strain, which caused a 2009 pandemic that killed more than 250,000 people.

MIT biological engineer Ram Sasisekharan, one of the study’s senior authors, has previously shown that airborne transmissibility depends on whether a virus’ hemagglutinin (HA) protein can bind to a specific type of receptor on the surface of human respiratory cells. Some flu viruses bind better to alpha 2-6 glycan receptors, which are found primarily in humans and other mammals, while other viruses are better adapted to alpha 2-3 glycan receptors, found predominantly in birds.

The 2009 strain was very good at binding to human alpha 2-6 receptors. In the new study, the researchers made four mutations in the HA molecule of this virus, which made it better suited to bind alpha 2-3 receptors instead of alpha 2-6. They then used it to infect ferrets, which are often used to model human influenza infection.

The researchers believed the mutated virus would not spread, but to their surprise, it traveled through the air just as well as the original version of the virus. After sequencing the virus’ genetic material, they found that it had undergone a genetic reversion that allowed its HA protein to bind to alpha 2-6 glycan receptors as well as alpha 2-3 glycan receptors.

“This is an experimental validation that gain of binding to the 2-6 glycan receptor is critical for aerosol transmission,” says Sasisekharan, the Alfred H. Caspary Professor of Biological Engineering and Health Sciences and Technology at MIT and a member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research.

Airborne evolution

The researchers then examined tissue from different parts of the respiratory tract and found that viruses with the genetic reversion were most abundant in the soft palate. By three days after the initial infection, 90 percent of the viruses in this region had the reverted form of the virus. Other sites in the respiratory tract had a mix of the two types of virus.

The researchers are now trying to figure out how this reversion occurs, and why it happens in the soft palate. They hypothesize that flu viruses with superior ability to transmit through the air outcompete other viruses in the soft palate, from which they can spread by packaging themselves into mucus droplets produced by cells in the soft palate known as goblet cells.

Now that the researchers have confirmed that viruses with the ability to bind to both alpha 2-6 and alpha 2-3 glycan receptors can spread effectively among mammals, they can use that information to help identify viruses that may cause pandemics, Sasisekharan says.

“It really provides us with a handle to very systematically look at any evolving pandemic viruses from the point of view of their ability to gain airborne transmissibility through binding to these 2-6 glycan receptors,” he says.

The study opens up “a new frontier in our fight against future emergence of pandemic influenza viruses,” says Lin-Fa Wang, director of the program in emerging infectious disease at Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School, who was not involved in the research.

“Taken together, these new findings have significantly contributed to our understanding of key mechanisms involved in the switching from non-airborne transmissible viruses to those capable of doing so,” Wang says. “It will be interesting to see whether the current findings can be corroborated in human infections.”