Team Identifies Structure of Tumor-Suppressing Protein

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

Their findings provide new insights into how the protein regulates cell growth and how mutations in the gene that encodes the protein can lead to cancer.

Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) is a known tumor suppressing protein that is encoded by the PTEN gene.

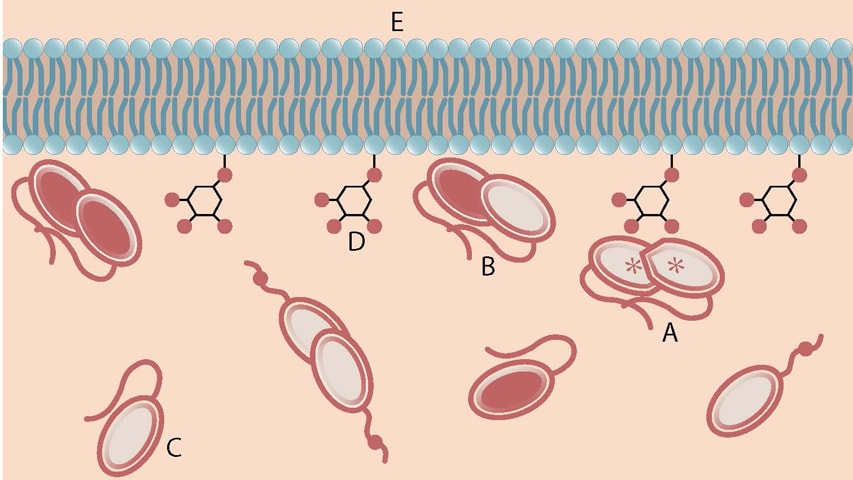

When expressed normally, the protein acts as an enzyme at the cell membrane, instigating a complex biochemical reaction that regulates the cell cycle and prevents cells from growing or dividing in an unregulated fashion. Each cell in the body contains two copies of the PTEN gene, one inherited from each parent. When there is a mutation in one or both of the PTEN genes, it interferes with the protein’s enzymatic activity and, as a result inhibits its tumor suppressing ability.

“Membrane-incorporated and membrane-associated proteins like PTEN make up one-third of all proteins in our body. Many important functions in health and disease depend on their proper functioning,” said Lösche, who with other researchers within Carnegie Mellon’s Center for Membrane Biology and Biophysics aim to understand the structure and function of cell membranes and membrane proteins. “Despite PTEN’s importance in human physiology and disease, there is a critical lack of understanding of the complex mechanisms that govern its activity.”

Recently, researchers led by Pier Paolo Pandolfi at Harvard Medical School found that PTEN’s tumor suppressing activity becomes elevated when two copies of the protein bind together, forming a dimeric protein.

“PTEN dimerization may be the key to understanding an individual’s susceptibility for PTEN-sensitive tumors,” said Lösche, a professor of physics and biomedical engineering at Carnegie Mellon.

In order to reveal how dimerization improves PTEN’s ability to thwart tumor development, researchers needed to establish the protein’s dimeric structure. Normally, protein structure is identified using crystallography, but attempts to crystallize the PTEN dimer had failed. Lösche and colleagues used a different technique called small-angle X–ray scattering (SAXS) which gains information about a protein’s structure by scattering X-rays through a solution containing the protein. They then used computer modeling to establish the dimer’s structure.

They found that in the PTEN dimers, the C-terminal tails of the two proteins may bind the protein bodies in a cross-wise fashion, which makes them more stable. As a result, they can more efficiently interact with the cell membrane, regulate cell growth and suppress tumor formation.

Now that more is known about the structure of the PTEN dimer, researchers will be able to use molecular biology tools to investigate the atomic-scale mechanisms of tumor formation facilitated by PTEN mutations. The researchers also hope that their findings will offer up a new avenue for cancer therapeutics.