Mass Extinctions Can Accelerate Evolution

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

Beyond its implications for artificial intelligence, the research supports the idea that mass extinctions actually speed up evolution by unleashing new creativity in adaptations.

Computer scientists Risto Miikkulainen and Joel Lehman co-authored the study which describes how simulations of mass extinctions promote novel features and abilities in surviving lineages.

“Focused destruction can lead to surprising outcomes,” said Miikkulainen, a professor of computer science at UT Austin. “Sometimes you have to develop something that seems objectively worse in order to develop the tools you need to get better.”

In biology, mass extinctions are known for being highly destructive, erasing a lot of genetic material from the tree of life. But some evolutionary biologists hypothesize that extinction events actually accelerate evolution by promoting those lineages that are the most evolvable, meaning ones that can quickly create useful new features and abilities.

Miikkulainen and Lehman found that, at least with robots, this is the case. For years, computer scientists have used computer algorithms inspired by evolution to train simulated robot brains, called neural networks, to improve at a task from one generation to the next. The UT Austin team’s innovation in the latest research was in examining how mass destruction could aid in computational evolution.

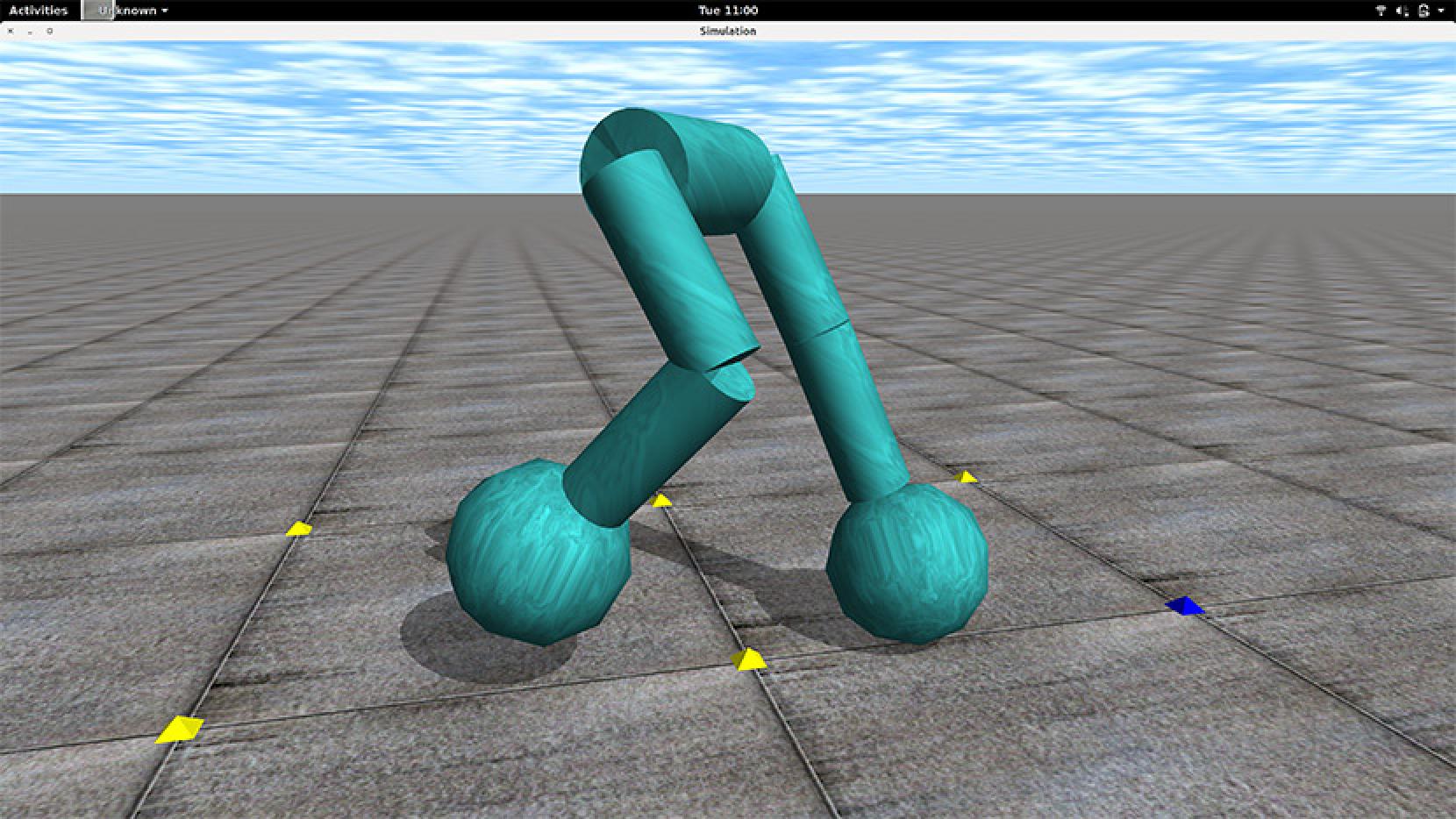

In computer simulations, they connected neural networks to simulated robotic legs with the goal of evolving a robot that could walk smoothly and stably. As with real evolution, random mutations were introduced through the computational evolution process. The scientists created many different niches so that a wide range of novel features and abilities would come about.

After hundreds of generations, a wide range of robotic behaviors had evolved to fill these niches, many of which were not directly useful for walking. Then the researchers randomly killed off the robots in 90 percent of the niches, mimicking a mass extinction.

After several such cycles of evolution and extinction, they discovered that the lineages that survived were the most evolvable and, therefore, had the greatest potential to produce new behaviors. Not only that, but overall, better solutions to the task of walking were evolved in simulations with mass extinctions, compared with simulations without them.

Practical applications of the research could include the development of robots that can better overcome obstacles (such as robots searching for survivors in earthquake rubble, exploring Mars or navigating a minefield) and human-like game agents.

“This is a good example of how evolution produces great things in indirect, meandering ways,” explains Lehman, a former postdoctoral researcher in Miikkulainen's lab, now at the IT University of Copenhagen. He and a former student of Miikkulainen’s at UT Austin, Kenneth Stanley, recently published a popular science book about evolutionary meandering, “The Myth of the Objective: Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned.” “Even destruction can be leveraged for evolutionary creativity.”