How to Tell “Fake” Olive Oils from the Genuine Article

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

With olive oil’s popularity on the increase in recent years largely owing to a range of perceived health benefits, some more tenuous than others, olive oil production and sales have become big business. However, it also opens the industry up to fraudsters looking to profiteer from this trend. Would you know if your “extra virgin” olive oil is exactly that, could you tell if it had been blended with cheaper alternatives?

To tackle this problem head on, scientists have been exploiting differences at the chemical level to expose adulterated products from the genuine article.

In a recent publication, a group from Wageningen University and Research in The Netherlands analysed 84 oil samples by gas chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (GC-MS/MS) to try and differentiate the processing grades of the oils contained by their chemical make-up.

Previously, a number of approaches have been taken to characterize adulterated oils based on the chemical biomarkers they contain but due to the natural variation within the oils, the acceptable range of measurements has remained broad. Consequently, the results obtained could not be relied upon as a method of fraud detection. To add further challenges for researchers, the refining process also removes a number of compounds unique to the differing grades, narrowing the possible pool of biomarkers that are available for differentiation.

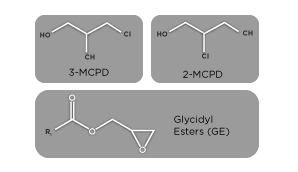

In this new study, the group identified that levels of three compounds, 2- and 3-monochloropropanediol (2- and 3-MCPD) esters and glycidyl esters (GEs) were significantly higher (P < 0.001) in the lower grade olive oils than in the extra virgin olive oils. The same observation was also made with the differing grades of vegetable oils.

Figure: This illustration shows the chemical structures of three compounds found in higher levels in lower quality olive and vegetable oils.

Figure: This illustration shows the chemical structures of three compounds found in higher levels in lower quality olive and vegetable oils.

MCPD esters and GEs are formed during the oil refinement process facilitated by the high temperatures and pressures involved. It therefore follows that the higher grade, cold-pressed oils that are not exposed to these conditions (not exceeding 27°C for extra virgin olive oil, 80°C for rapeseed oil and 40°C for sunflower oil), or to lesser extents will contain lower levels of these biomarkers. Prior to this study these targets had received little attention.

Calculations revealed that adulteration of extra virgin olive oils with just 2%, 5% and 13-14% of cheaper refined oils could be detected using the 3-MCPD ester, 2-MCPD ester and GE biomarkers respectively. Furthermore, these compounds are difficult to remove from refined oils, making subversion by fraudsters using this method uneconomical.

Taken together, these findings suggest that quantification of 2- and 3-MCPD esters and GEs offer a promising and sensitive target for fraud detection where higher grade oils have been substituted with cheaper, lower grade refined products. This provides scientists and genuine producers with another weapon in their armoury for the fight against fake products and takes consumers a step closer to reassurance that they are getting what they paid for.