Just a Gut Feeling: IBS, SIBO and the Gut-Brain Connection

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

People often talk about their “gut instincts” or how they just “felt it in my guts” or that stress can give you “butterflies in the stomach” or make you nauseous to the point of vomiting.

Are these just figures of speech?

It turns out that the gut – the digestive system – has its own nervous system that is often referred to as our “second brain”. This “second brain” is called the enteric nervous system (ENS) and research is revealing that the ENS is in direct communication with the brain and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (part of the central nervous system or CNS), the gut microbiota, the hormonal and the immune systems.

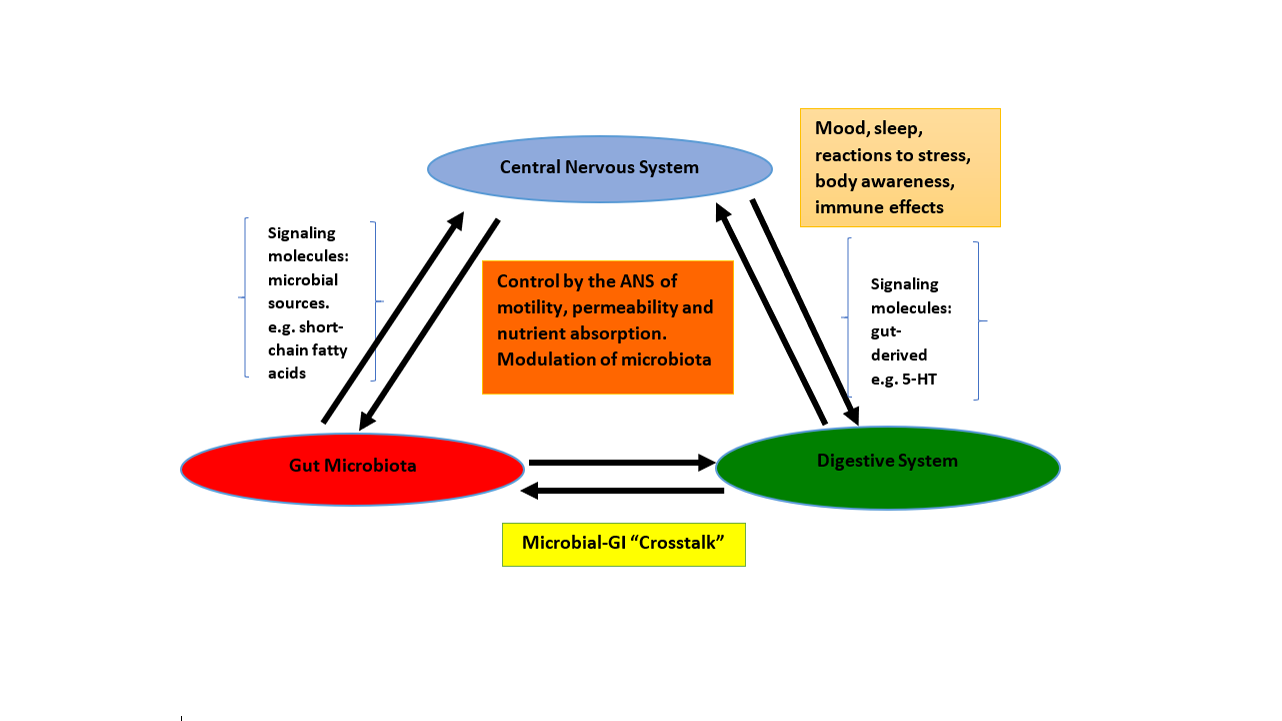

These are two-way communications systems, so that, for example, the microbiota – the combined pattern of microbes in the gut – can affect the stress response, the immune response, hormonal control of digestion and the predisposition to various conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, obesity, diabetes, depression and anxiety. In turn, the ENS – and likely the CNS – can affect the pattern of bacteria in the microbiome as well as the digestive processes of the gut. However, it is becoming clearer that this is only the tip of the iceberg – the ENS, CNS and the microbiota can interact to produce dysfunction in the digestive, neurological, immune and hormonal systems, and to affect mental health.

The HPA axis is central in controlling the response to stress – and, as evidenced by the phrases like “my guts were tied in knots” or “I saw the accident and my stomach just dropped” – is both affected by and has effects on the ENS. The stress response – controlled in major part by the HPA axis – can be directly affected by abnormal gut bacteria early in life.

Serotonin (5HT) – a neurotransmitter sometimes called the “happiness hormone”, affecting mood, depression and anxiety – is found in its highest concentrations in the gut. A recent study from CalTech found that bacteria in the gut play a “critical role in regulating host 5-HT.” The microbiome is implicated in both anxiety and depression, disorders where 5-HT can play a critical role.

Recently, a systems biological model (the Brain-Gut-Microbiome or BGM model) was proposed that “posits circular communication loops amid the brain, gut, and gut microbiome, and in which perturbation at any level can propagate dysregulation throughout the circuit. A series of largely preclinical observations implicates alterations in brain-gut-microbiome communication in the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome, obesity, and several psychiatric and neurological disorders. Continued research holds the promise of identifying novel therapeutic targets and developing treatment strategies to address some of the most debilitating, costly, and poorly understood diseases.”

IBS and SIBO: Is there a connection?

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional bowel disorder characterized by abdominal pain, cramping, bloating, gas, diarrhea, constipation or both. The abdominal pain and cramping are typically relieved by a bowel movement, that movement often producing a stool covered in mucus. Part of the underlying dysfunction in IBS is neurological. Diagnosis is often by exclusion as there is no specific diagnostic test for any form of IBS – diagnosis is based on the pattern of symptoms and the duration of the pattern. The Rome IV Criteria are used: “Recurrent abdominal pain, on average, at least 1 day per week in the last 3 months, associated with 2 or more of the following*:

- Related to defecation

- Associated with a change in frequency of stool

- Associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool

* Criteria fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis.

The causes of IBS remain unclear, though abnormal gastrointestinal (GI) motility and a disruption in the gut-brain axis (the BGM) appear to be at the root of IBS. It is often associated with depression and anxiety along with abnormalities in the microbiota. Risk factors for IBS include SIBO (see below), a history of viral or bacterial infections and abnormal motility of the small and large intestines.

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) is an excess of bacteria – sometimes methane-producing bacteria and more often with hydrogen-producing bacteria – in the small intestine – a portion of the digestive system that normally has few bacterial or other microbial residents. SIBO can lead to increased gas, diarrhea or constipation, abdominal pain, nausea and fatigue. Risk factors for SIBO include IBS, other GI disorders, and multiple courses of antibiotics. SIBO is believed to be related to dysfunction of small intestinal motility – the research community links IBS and SIBO because of the similarity of the symptoms with some believing that IBS is the primary event predisposing to SIBO where others believe just the opposite – that SIBO is the primary event predisposing to IBS. IBS patients with SIBO usually have to combine multiple different treatment options to manage and maintain health. Further research is needed to unravel the answers to this complex disorder.

A systems biology view of IBS and SIBO

IBS and SIBO are clearly related by symptoms and likely related mechanistically. The interconnectedness and bidirectionality of the Brain-Gut-Microbiome is currently being extensively studied – much more needs to be learned. Understanding the interactions will likely prove crucial to understanding functional digestive disorders and how stress can impact health.

While the initial cause(s) of IBS and SIBO are not known, it is becoming clearer that the gut, the brain and the microbiota communicate with each other – and that if this communication breaks down and becomes dysfunctional, dysfunction in the digestive, neurological, and immune system can become disrupted. Mental health may suffer as well as can sleep and the reactions to stress.

One should be cautious in applying pre-clinical information from model systems to clinical situations, yet maintaining a healthy microbiota has been clearly implicated in many conditions including functional digestive disorders such as SIBO and IBS, mood disorders, autism, obesity, addiction, allergic disorders, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, conditions associated with aging and others.