UW Gets NOAA Grant for Algal Bloom Forecasts

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

A new NOAA-sponsored University of Washington project brings together academic, federal, state and tribal scientists to develop forecasts for toxic harmful algal blooms in the Pacific Northwest, like the massive bloom that closed Pacific Northwest beaches to shellfish harvesting in summer 2015.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in August has awarded a five-year, $1.3 million grant to start working on the forecasts. The new early warning system will transition to operation starting in 2017.

Once up and running, the forecasts will help coastal communities from Neah Bay, Washington, to Newport, Oregon, target their shellfish monitoring and fine-tune decisions about closing beaches to shellfish harvesting to have more advance warning and potentially avoid some beach closures.

“This will be a sort of weather forecast for Pacific Northwest harmful algal blooms,” said Parker MacCready, a UW professor of oceanography and member of the UW Coastal Modeling Group.

Forecasts will be produced by the UW’s LiveOcean model, which creates three-day forecasts for Washington and Oregon coastal waters. The model provides results for open-ocean beaches as well as complex protected waterways — including Willapa Bay and Grays Harbor — that are home to many of the region’s shellfish beds.

Up-to-date monitoring of offshore conditions will be provided by Vera Trainer, a biologist at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center, and members of the Makah Tribe. Starting this spring, they will collect samples by ship every two weeks in an eddy near the mouth of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, which has been identified as a source of toxin-producing algae that can reach local beaches. The team will then analyze water samples within a day at the Makah Tribal lab in Neah Bay.

The new collaboration “will bring the most powerful technologies for cell and toxin detection to our partners who are directly impacted by these blooms,” Trainer said. “This will help the tribe and all coastal managers make rapid, informed decisions about seafood safety.”

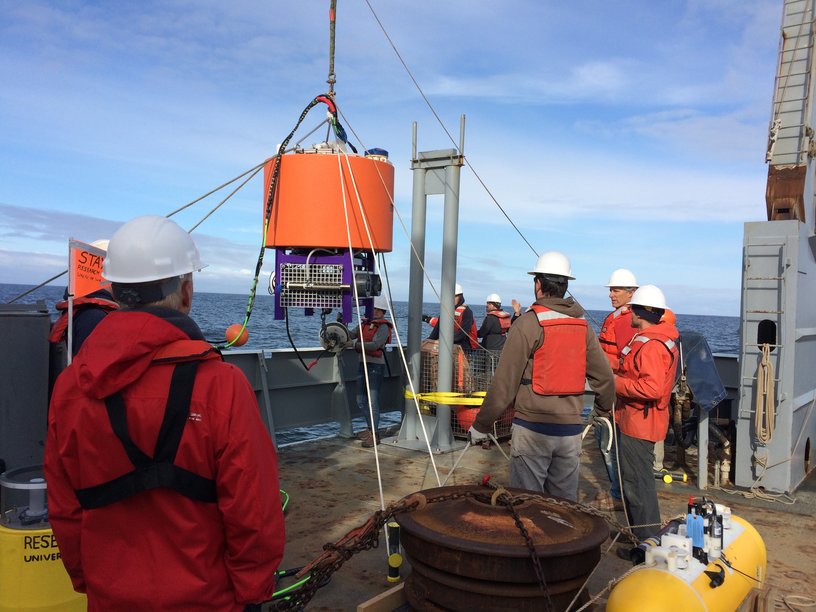

At the UW, MacCready will work with oceanographers Ryan McCabe, at the UW’s Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean, and Barbara Hickey, in the School of Oceanography, to combine their LiveOcean model with those water sample results and other information, including beachside monitoring by the Washington Olympic Region Harmful Algal Blooms program and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, and real-time data from a NOAA offshore robot, the Environmental Sample Processor, launched in May by the UW and NOAA.

The team will use the LiveOcean model to produce a forecast mapping toxicity risk leading up to each scheduled razor clam dig, in the form of a bulletin for coastal resource managers.

“This really is the culmination of more than a decade of basic research on the physics and biology behind these toxic blooms,” said project co-lead Neil Banas, a former UW scientist now based at the University of Strathclyde in Scotland.

A previous version of the HAB Bulletin was produced by Hickey and Trainer from 2008 to 2011 with funding from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The new project is funded by NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, through its Monitoring and Event Response for Harmful Algal Blooms research program.

“We are excited to help bring about reliable predictions of when and where these toxic blooms can be expected, as it will help us better provide our citizens safe access to some of the best seafood in the world,” said Matt Hunter, a shellfish biologist with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.