Simple Urine Test Predicts Bladder Cancer Years Before Diagnosis

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

Researchers have identified 10 genetic mutations that can predict the most common type of bladder cancer up to 12 years prior to diagnosis. The study results were presented at the European Association of Urology (EAU) annual Congress in Milan.

Towards earlier diagnosis of bladder cancer

Early diagnosis of bladder cancer is imperative, as only 50% of patients diagnosed with advanced cancer will survive five years or more. Detecting bladder cancer in its early stages can increase this survival rate to 80%, but current clinical methods are sub-optimal. “Diagnosis of bladder cancer relies on expensive and invasive procedures such as cystoscopy, which involves inserting a camera into the bladder,” says Dr. Florence Le Calvez-Kelm, a cancer genomics scientist at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).

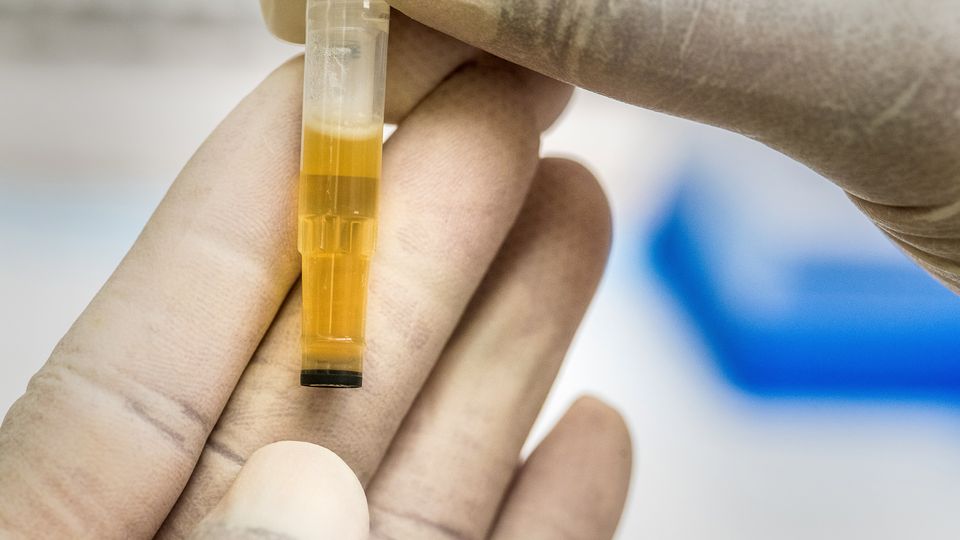

Alternative, more simplistic methods – such as a urine test – are desirable for accurately diagnosing or predicting bladder cancer as early as possible. Le Calvez-Kelm is the lead scientist on a new collaborative research project exploring the utility of an existing urine test called UroAmp, which was developed by a Oregon Health Science University spin out company.

Want more breaking news?

Subscribe to Technology Networks’ daily newsletter, delivering breaking science news straight to your inbox every day.

Subscribe for FREEUroAmp is described as “a urine comprehensive genomic profiling test” that can identify mutations across 60 different genes. Le Calvez-Kelm and colleagues at the Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Iran, informed by their previous work exploring genetic mutations linked to bladder cancer, reduced the number of mutations analyzed by the test to 10 genes.

New test predicts cancer in 66% of patients

The researchers first trialed the effectiveness of the test in participants of the Golestan Cohort Study, which has gathered data on over 50,000 participants over a 10-year period. At the first stage of recruitment, all study participants were asked to submit a urine test.

Forty patients in the Golestan Cohort Study received a diagnosis of bladder cancer. Le Calvez-Kelm and colleagues accessed urine samples from 29 of the patients to apply their novel test, in addition to urine samples from 98 other participants that could be used as controls. They found that the test could predict future bladder cancer in 19 (66%) of the patients, despite the urine samples being obtained 12 years prior to the clinical diagnosis. Of the 40 bladder cancer patients, 14 had been diagnosed within 7 years of the urine being collected. In this instance, the urine test could predict cancer in 12 (86%) of the patients. In the control population, the test was accurately negative in 96% of patients who did not develop cancer in the future.

Urine test less invasive and most cost-effective

The urine test was also applied in 70 bladder cancer patients and 96 controls from Massachusetts General Hospital and Ohio State University. These samples were taken on the day that the patients received their diagnosis prior to cystoscopy procedures. Using the novel test, genetic mutations were identified in samples from 50 (71%) of the participants whose tumors were detected during the cystoscopy, and mutations were not found in 90 (94%) of the control participants.

“We’ve clearly identified which are the most important acquired genetic mutations that can significantly increase the risk of cancer developing within 10 years. Our results were consistent across two very different groups – those with known risk factors undergoing cystoscopy and individuals who were assumed to be healthy,” Le Calvez-Kelm says on the potential of the test.

The research team suggest that, should their data be replicated in larger cohorts, simple urine tests could help routine screening for those at high-risk of bladder cancer, including smokers or individuals exposed to carcinogens.

“This kind of test could also be used when patients come to their doctors with blood in the urine, to help reduce unnecessary cystoscopies. If we can identify bladder cancer early on, before the disease has advanced, then we can save more lives,” adds Le Calvez-Kelm.

“Research of this nature is very encouraging as it shows that our ability to identify molecular alterations in liquid biopsies such as urine that might indicate cancer is constantly improving,” adds Dr. Joost Boormans, a member of the EAU Scientific Congress Office and a urologist at the Erasmus University Medical Center Rotterdam. “A simple urine test would be far easier for patients to undergo than invasive procedures or scans, as well as being less costly for health services.”

This article is a rework of a press release issued by the European Association of Urology. Material has been edited for length and content.