The Future of Neurotechnology: What I’ve Learned As a Gen-Z, Early-Stage Founder

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

In this comment piece, Hubly Surgical CEO Casey Grage gives a perspective on her advancing career, which has seen her go from freshman to startup co-founder in just a few years.

Growing up, I was the world’s biggest Indiana Jones fan. I dreamt of roaming the globe, charting maps and sketching pictures of deserted ruins. I was heartbroken when Nat Geo Wild informed me the world’s landmass is already entirely mapped, but I rebounded quickly. Biologists, I knew, spent months exploring rainforests and arctic deserts in search of new species. To prepare myself, I tied knots and climbed trees. I tried surviving in the wild on summer days by only eating food out of my mom’s garden. I also focused my attention on learning science. It was the early 2000s. In our home office, my family had one printer and one dinosaur computer, which was my dad’s primary work station. Like boomers today, I thought Google was the internet. I spent hours a day conducting literature reviews: image searching various animals and printing the photos. I stored these printouts in my bedroom in manila folders I had found in the office. Next to them were notebooks of my research: handwritten exact copies of the Magic Treehouse Research Guide series. There is even a notebook in which I repeatedly wrote the names of 20 sharks in serial killer fashion. I knew biologists needed that kind of thing memorized.

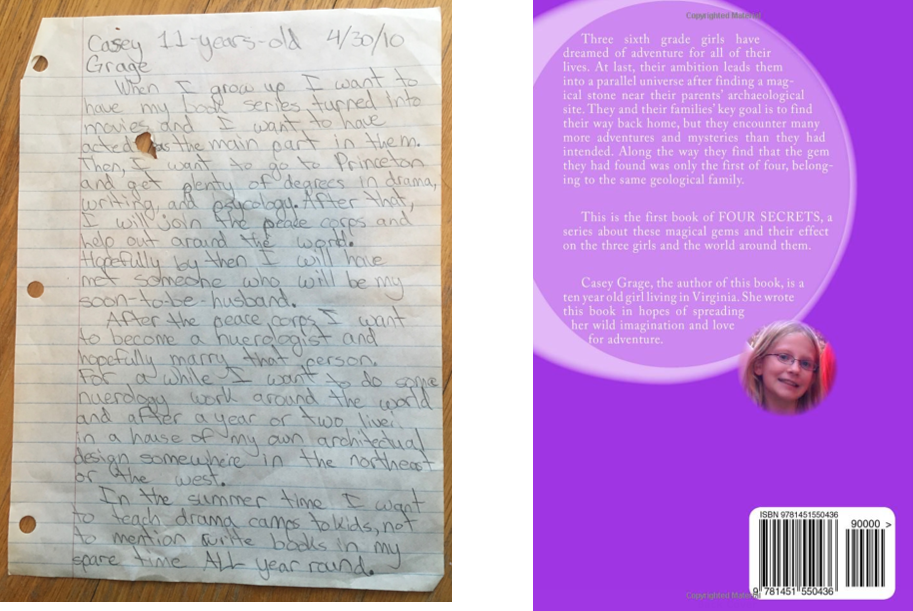

At the age of 8, I began writing a book about three girls who traverse the dangerous terrains I had studied (called Adventure At Last, still available for purchase on Amazon!). I learned that most biologists work in labs, not in rainforests, but I was okay with that. I am told I was 9 or 10 when I began announcing my future PhD in neurology. I loved, and still love, neuroscience because it is the perfect intersection of philosophical mystery, awesome innovation, and tangible advancements for peoples’ lives.

Several years later, I was a freshman at Northwestern University with a declared major in neuroscience. I had been conducting part-time neuroscientific research in my dream lab. My grades needed to improve, and I was stressed and overworked, but I was on the right path. The plan was to do a senior research thesis through this lab, get my PhD, do a post-doctoral fellowship, and work as a professor to establish myself as a real neuroscientist. Then, I would have the knowledge and reputation to be Chief Science Officer of a neurotechnology startup, and then, I would have the ideas and knowhow to found my own company. That’s still sort of the plan. I just expedited the process a bit.

NUvention Medical is a six-month Northwestern course structured after the Stanford Biodesign model of medtech startup creation. The course is cross-listed across the business, law, medical, and engineering schools. In the first few weeks, students form teams with at least one person from each discipline. The teams each shadow the medical student of the group and work to identify a clinical need. Then, the teams develop the solution and the business plan. Despite the course being listed as for graduate students only, I applied, and was accepted.

Left: Personal Statement by Casey Grage, 2010. Right: Back Cover of Adventure at Last

The course began in Fall 2017, and it was rough. I knew the networking and team formation would be the most difficult part for me as the only person in the room without a bachelor’s degree. For three weeks, I was in “Groundhog Day,” doomed to a cycle of meeting potential team-mates and being passed over for medical students with more experience. I soon realized I needed to have an idea good enough to warrant overlooking my inexperience. I brainstormed, and at the beginning of each class, I pitched neurotechnology companies.

Eventually, Amit (Ayer) and Jack (Mahoney) approached me after one of these pitches. Amit said, “You seem smart and interested in neurology. I’m a neurosurgeon at Northwestern, and I’m friends with Jack through our MBA night classes. Do you want to be on our team?” I lucked out here. They could have easily asked me for my resume or my background, followed by fake smiles and coincidentally seeing someone they needed to talk to. They didn’t, or maybe they didn’t care. With Jack’s and Amit’s years of experience in neurosurgery, entrepreneurship, and finance, we were able to easily attract Nate (Andrews) and Nisar (Parekh) to the team.

In brainstorming neurosurgical device ideas, Amit mentioned that the ventriculostomy is the most common neurosurgery, and it sucks. After minimal research, we discovered the ventriculostomy has one of the highest rates of failure of any surgery. It results in hemorrhage, brain infection, stroke, or death up to 50% of the time it is performed. The current standard of care is the Integra Lifesciences Cranial Access Kit, a free-hand, hand-cranked drill. How a ventriculostomy works with this current solution is a neurosurgeon, like Amit, meets you at your hospital bedside and manually cranks a hole through your skull without any features for guidance or stability. The Integra Cranial Access drill’s lack of safety features allows failure due to human error. This means that the bedside ventriculostomy, which is often not performed by experienced neurosurgeons, but rather by general surgeons, trauma clinicians and junior residents, is incredibly dangerous.

We quickly learned the ventriculostomy is not unique. This antiquity is what bedside neurosurgery looks like as a field. Our big picture is to revolutionize the field of bedside neurosurgery, beginning with the medieval ventriculostomy. In these early weeks of NUvention, our clinical need was clear and focused to that one procedure. Even so, pricing our novel device within a 10% margin of the inexpensive, current, hand-cranked solution presented a market opportunity of approximately $8 billion for the ventriculostomy alone. Now, we just had to create that device.

I worked my ass off. I had never been more sleep-deprived, anxious, or overworked in my life than I was during those first three months. I was taking the maximum course load at Northwestern, researching at my lab part-time, and on the executive board of four student organizations. I felt that I was in the bottom tier of all my classes. I knew I was the least accomplished in NUvention, and probably in my engineering course as well. I ended up receiving my lowest GPA for any quarter thus far (and every quarter after). I felt dumb, and above all, I was tired. When winter break rolled around, I did nothing but sleep for nearly three weeks. If I could do it all over again, I would’ve reprioritized. Taken one less class. My point is startups are hard. The learning curve was huge. Imposter syndrome is real. But as we entered the second quarter of the course, I realized we might actually be able to file a patent. Nate had years of patent agent experience, and our product idea was up to the mark.

We had invented an integrated drilling system, which we named Ventri Drill, to replace the Integra hand-cranked drill. We included five key features driven by surveys and interviews with neurosurgeons at different institutions: plunge protection, which automatically, immediately retracts the drill bit once it breaks through the skull, drilling guidance, catheter guidance to mitigate the number of holes poked into the brain and additional features for ease of use. And, of course, it’s battery powered.

We garnered attention from a few key opinion leaders. Most notably, the two vice chairs of neurosurgery at Northwestern Hospital, Dr. James Chandler and Dr. Babak Jahromi, became our advisers and two of our strongest advocates. Their support was in itself market validation, but they also helped push our product and business development to the best versions they could be.

The course came to an end, and we decided to continue. We were very successful in the pitch competition circuit. We decided to incorporate the company, now named Hubly, and declare official roles. Now, Nate and Jack had children. Amit was a neurosurgeon. Nisar was considering a full-time job at Pfizer. I was graduating a year early, had no dependents, and was more excited about Hubly than anything in my life. The person who would take the risk first and go full-time would be me. I advocated for myself. I was essential in building our proof-of-concept and in getting this pitch competition money, I said. I am passionate about Hubly like no other, and I am capable. I’m level-headed, I know my limitations, and I’ll ask for help when needed. Above all, with my productivity complex, I get shit done. I was selected as CEO.

Time went by and my team continued to make progress building Hubly. I grew more passionate and more confident in our company’s success. I grew impatient. Egotistically, I thought, “Patients are dying every day our product is not on the market!” There was no time to waste. I applied to accelerators. I was ready to go full-time on Hubly regardless of our admittance to one, but after all, having the financial and resource support of an accelerator would be a beneficial kickstart. In October 2019, we were part of the 4% of applicants admitted to the world-renowned, platinum-ranked accelerator, Alchemist, our first source of significant funding.

It is now January 2020. I have turned down acceptance to a Columbia graduate degree program, left my six-figure salary, and uprooted my life in Chicago for this brain drill startup. In the past month we’ve raised nearly $200,000. I’ll be in San Francisco for the next 6 months for the Alchemist program, and indefinitely after. The plan is to grow Hubly for the next decade (or longer), get a PhD in neuroengineering, and start another medtech company.