Brain Scan Surgeons to Find the Best

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

A non-invasive brain imaging technique for evaluating surgical competency objectively and accurately assessed surgical skill levels among surgeons and medical students with varying ranges of expertise, researchers report.

They say their approach – which analyzes brain activity in real-time while study subjects carried out a complex surgical motor task – outperforms currently used methods that measure performance for board certification in general surgery.

Demonstrating proficiency in the Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) is currently required for certification in general surgery by the American Board of Surgery, yet the surgical skill scoring component of the FLS program is under scrutiny because of subjectivity in scoring and inconsistencies in FLS score interpretations.

Arun Nemani and colleagues addressed these inadequacies by comparing surgical motor skill levels in two groups of individuals: expert versus novice surgeons and trained versus untrained medical students.

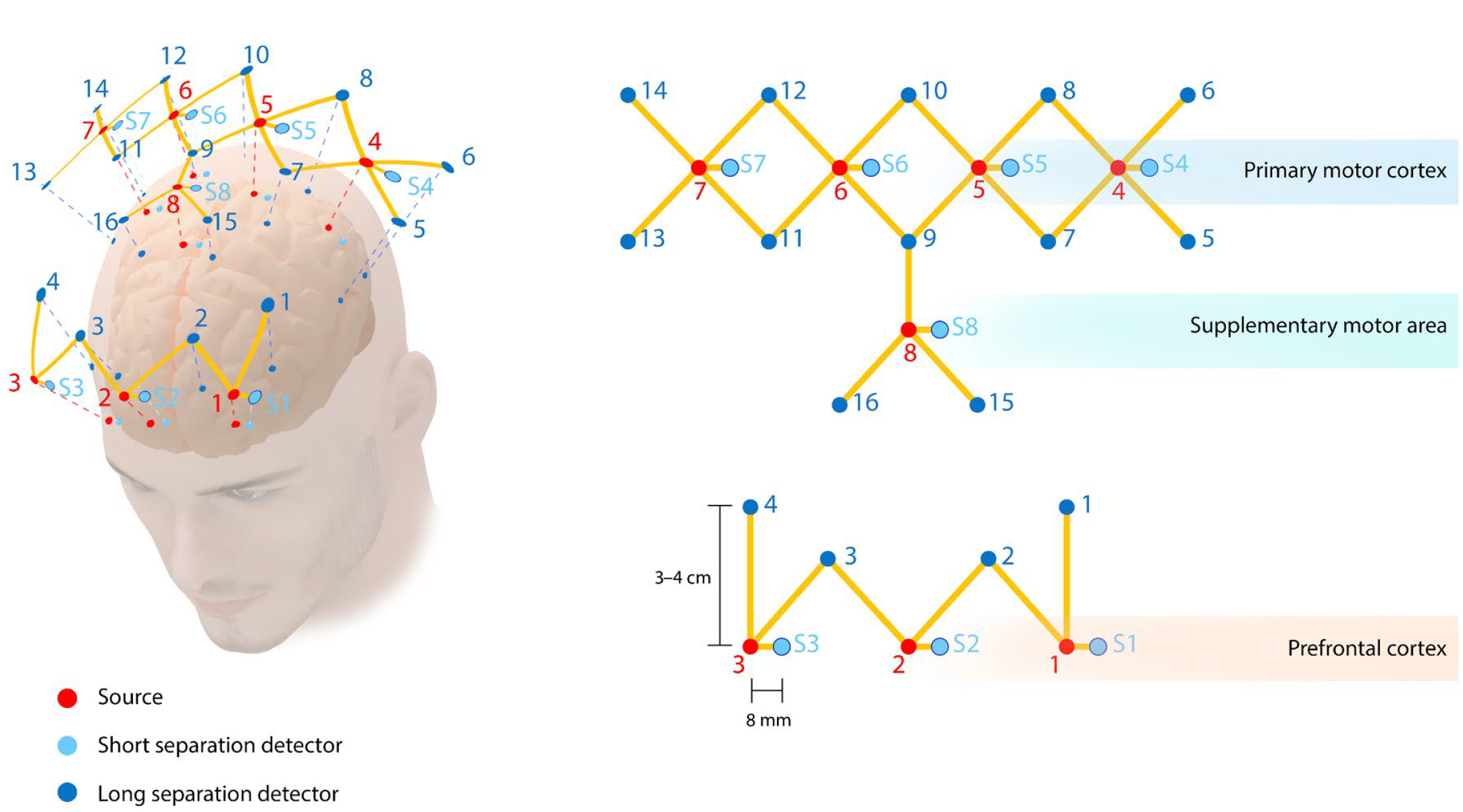

Optode positions for coverage over the PFC, M1, and SMA. Red dots indicate infrared sources, blue dots indicate long separation detectors, and textured blue dots indicate short separation detectors. The PFC has three sources (1 to 3), three short separation detectors (S1 to S3), and four long separation detectors (1 to 4). The M1 has 4 sources (4 to 7), 4 short separation detectors (S4 to S7), and 10 long detectors (5 to 14). The SMA has one source (8), one short separation detector (S8), and three long separation detectors (9, 15, and 16). Credit: Nicolás Fernández, Nemani et al.

Optode positions for coverage over the PFC, M1, and SMA. Red dots indicate infrared sources, blue dots indicate long separation detectors, and textured blue dots indicate short separation detectors. The PFC has three sources (1 to 3), three short separation detectors (S1 to S3), and four long separation detectors (1 to 4). The M1 has 4 sources (4 to 7), 4 short separation detectors (S4 to S7), and 10 long detectors (5 to 14). The SMA has one source (8), one short separation detector (S8), and three long separation detectors (9, 15, and 16). Credit: Nicolás Fernández, Nemani et al.

The scientists showed that an imaging method called functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) appropriately classified surgical expertise in both sets of participants. Nemani et al. compared fNIRS to FLS (the standardized test of surgical competency) among the two cohorts during a surgical cutting procedure, an experimental setup that allowed them to discriminate between established skill levels, in addition to evaluating expertise as it was being acquired.

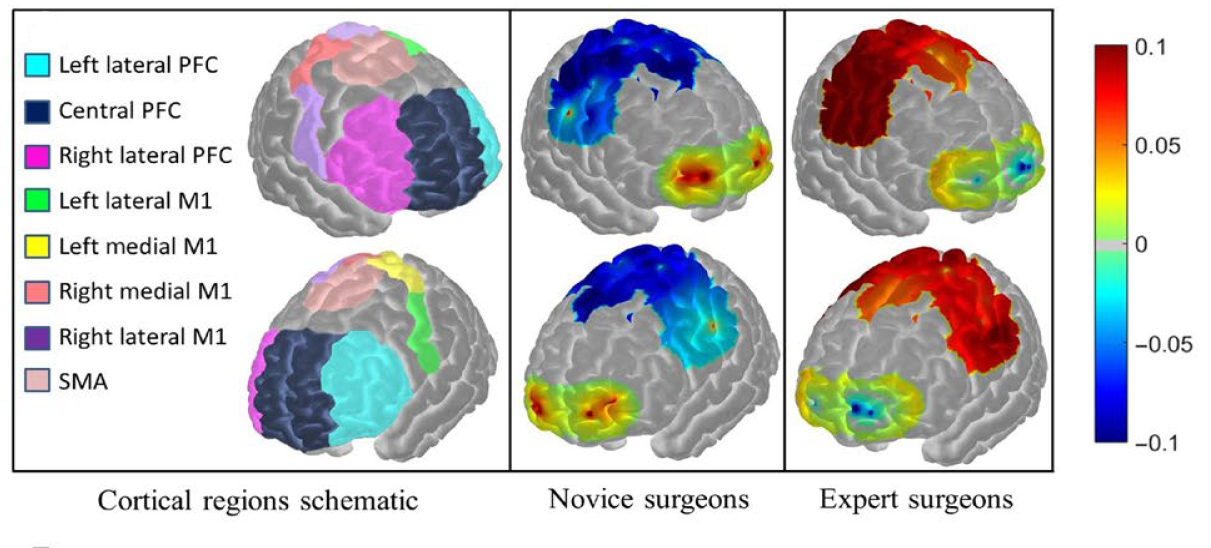

Interestingly, novice surgeons and unskilled medical students demonstrated increased brain activity in the prefrontal cortex (where planning complex behavior occurs) and decreased brain activity in the primary motor cortex (a key area involved in motor function) and supplemental motor area (that contributes to control of movement), in contrast to expert surgeons and skilled medical students.  Brain region labels are shown for PFC, M1, and SMA regions. Average functional activation for all subjects in the Novice and Expert surgeon groups are shown as spatial maps while subjects perform the FLS task. Credit: Nemani et al.

Brain region labels are shown for PFC, M1, and SMA regions. Average functional activation for all subjects in the Novice and Expert surgeon groups are shown as spatial maps while subjects perform the FLS task. Credit: Nemani et al.

The authors note that fNIRS could be expanded to identify and predict those who may achieve faster learning curves for mastering complex surgical skills.

This article has been republished from materials provided by the open-access journal Science Advances. Note: material may have been edited for length and content. For further information, please contact the cited source.