How Human Cognition Has Changed How We Draw Portraits

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

Throughout history, portraits featuring the human profile have evolved to reflect changing cultural norms. A new study led by Helena Miton, a Santa Fe Institute Omidyar Fellow, and co-authored by Dan Sperber of Central European University and Mikolaj Hernik, of UiT the Artic University of Norway, shows that human cognition plays a critical role in the evolution of human portraiture.

"These cognitive factors cause greater spontaneous attention to what is in front of -- rather than behind -- a subject, Miton says. "Scenes with more space in front of a directed object are both produced more often and judged as more aesthetically pleasant. This leads to the prediction that, in profile-oriented human portraits, compositions with more space in front of depicted subjects (a 'forward bias') should be over-represented."

To test their prediction, the research team looked at 1831 paintings by 582 unique European painters from the 15th to the 20th century. They not only found evidence that this forward bias -- where painters put more open space in front of their sitters than behind them -- was widespread, they also found evidence that the bias became stronger when cultural norms of spatial composition favoring centering became less stringent.

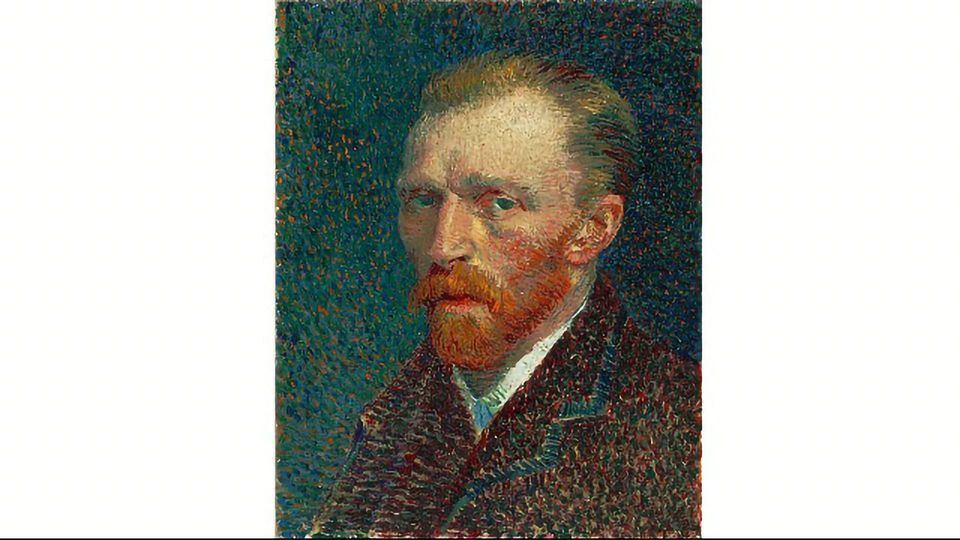

In the accompanying image, the portrait on the left (Adrian Brouwer, 1630) is an example of a composition with the sitter centered. On the right, a portrait by Pierre Auguste Renoir (1905) shows the forward bias, with more free space in front of the sitter than behind her. The study showed this type of spatial composition increased over time.

"Culture and cognition are two interacting domains," Miton explains. "With most cultural phenomena, you're going to have some kind of influence from cognition. Our idea is to work out how we identify these factors and how we work with that type of causality."

The research team identified cultural norms that favored centering portraits, especially in the earlier periods. These preferences clearly loosened over time, resulting in more diverse portrait composition.

The widespread presence of a forward bias was robust. Previous studies found some evidence of a forward bias in the production of a handful of painters, but these results suggest that this bias in spatial composition was widespread--particularly remarkable since it goes against a cultural norm that favors centering sitters.

According to Miton, this research approach can be extended to quantify in a more general way (and with a more general painting data set) how much artistic norms loosen and how much variation increases over time. Beyond the art world, the approach can also look at the role cognition plays in other cultural phenomena, from writing systems to medical practices.

Reference: Miton, H., Sperber, D., & Hernik, M. (2020). A Forward Bias in Human Profile-Oriented Portraits. Cognitive Science, 44(6), e12866. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12866

This article has been republished from the following materials. Note: material may have been edited for length and content. For further information, please contact the cited source.