New Images Reveal Structures of Critical Brain Receptors

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

New images from scientists at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) reveal for the first time the three-dimensional structures of a set of molecules critical for healthy brain function. The molecules are members of a family of proteins in the brain known as NMDA receptors, which mediate the passage of essential signals between neurons. The detailed pictures generated by the CSHL team will serve as a valuable blueprint for drug developers working on new treatments for schizophrenia, depression, and other neuropsychiatric conditions.

“This NMDA receptor is such an important drug target,” says Tsung-Han Chou, a postdoctoral researcher in CSHL Professor Hiro Furukawa’s lab. That’s because dysfunctional NMDA receptors are thought to contribute to a wide range of conditions, including not just depression and schizophrenia, but also Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, and seizures. “We hope our images, which visualize the receptor for the first time, will facilitate drug development across the field based on our structural information,” Chou says.

NMDA receptors are found on neurons throughout the brain. When activated by a signaling molecule known as glutamate—one of the brain’s many neurotransmitters—the receptor changes shape, opening a channel into the cell. This increases the likelihood that the neurons will fire off a signal to neighboring cells. Communication between neurons is critical for everything from movement to memory. Dysfunction and disease can result when NMDA receptors cause either too much neural communication or too little.

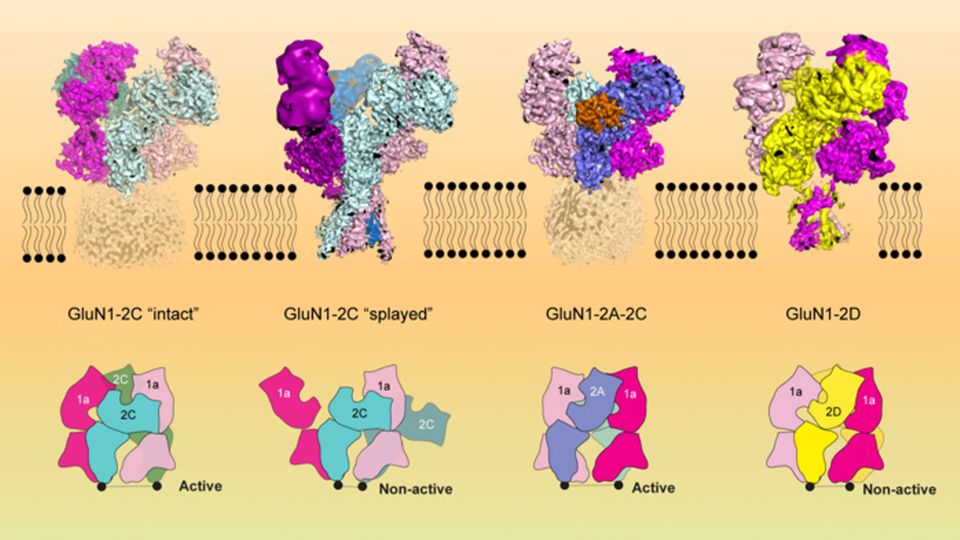

“GluN1-2C, GluN1-2A-2C, and GluN1-2D NMDA receptors exist in discrete brain regions, such as the cerebellum, at a defined period during brain development,” Furukawa explains. “It is hypothesized that abnormally low-functioning NMDA receptors containing GluN1-2C cause schizophrenia-like symptoms.”

While some NMDA receptors’ structures are better studied, less was known about those that Furukawa’s team focused on in their new study. A more complete picture was needed because the ability to target specific types of NMDA receptors would give pharmaceutical developers greater control over where in the brain a potential drug will be active. And when it comes to developing better therapies, Chou says, “the more information we can get, the better.”

Furukawa, Chou, and their colleagues used a method called cryo-electron microscopy to capture a series of images of the receptors, which reveal their shapes in exquisite detail. Some images show the receptors grasping glutamate, the natural neurotransmitter that switches them on; others show the receptors activated by a molecule used in the lab to enhance NMDA signaling. By revealing exactly where and how those molecules interact, the new pictures will help guide the design of potential therapies that switch off overactive NMDA receptors or turn on those that aren’t active enough.

This article has been republished from the following materials. Note: material may have been edited for length and content. For further information, please contact the cited source.