In search of tinnitus, that phantom ringing in the ears

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

About one in five people experience tinnitus, the perception of a sound--often described as ringing--that isn't really there. Now, researchers reporting in the Cell Press journal Current Biology have taken advantage of a rare opportunity to record directly from the brain of a person with tinnitus in order to find the brain networks responsible.

The observations reveal just how different tinnitus is from normal representations of sounds in the brain.

"Perhaps the most remarkable finding was that activity directly linked to tinnitus was very extensive, and spanned a large proportion of the part of the brain we measured from," says Will Sedley of Newcastle University. "In contrast, the brain responses to a sound we played that mimicked [the subject's] tinnitus were localized to just a tiny area."

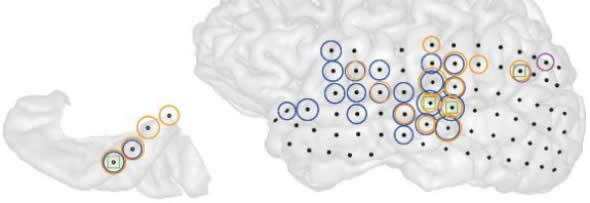

This is a 3-D image of the left brain hemisphere of a patient with tinnitus (right) and the part of that hemisphere containing primary auditory cortex (left). Black dots indicate all the sites recorded from. Colored circles indicate electrodes at which the strength of ongoing brain activity correlated with the current strength of tinnitus perceived by the patient. Different colors indicate different frequencies of brain activity (blue = low, magenta = middle, orange = high) whose strength changed alongside tinnitus. Green squares indicate sites where the interaction between these different frequencies changed alongside changes in tinnitus. Credit: Sedley, W et al.

In the new study, Sedley and The University of Iowa's Phillip Gander contrasted brain activity during periods when tinnitus was relatively stronger and weaker. The study was only possible because the 50-year-old man they studied required invasive electrode monitoring for epilepsy. He also happened to have a typical pattern of tinnitus, including ringing in both ears, in association with hearing loss.

"It is such a rarity that a person requiring invasive electrode monitoring for epilepsy also has tinnitus that we aim to study every such person if they are willing," Gander says.

The researchers found the expected tinnitus-linked brain activity, but they report that the unusual activity extended far beyond circumscribed auditory cortical regions to encompass almost all of the auditory cortex, along with other parts of the brain.

The discovery adds to the understanding of tinnitus and helps to explain why treatment has proven to be such a challenge, the researchers say.

"We now know that tinnitus is represented very differently in the brain to normal sounds, even ones that sound the same, and therefore these cannot necessarily be used as the basis for understanding tinnitus or targeting treatment," Sedley says.

"The sheer amount of the brain across which the tinnitus network is present suggests that tinnitus may not simply 'fill in' the 'gap' left by hearing damage, but also actively infiltrates beyond this into wider brain systems," Gander adds.

These new insights may help to inform treatments such as neurofeedback, where patients learn to control their "brainwaves," or electromagnetic brain stimulation, according to the researchers. A better understanding of the brain patterns associated with tinnitus may also help point toward new pharmacological approaches to treatment, "which have so far generally been disappointing."

Note: Material may have been edited for length and content. For further information, please contact the cited source.

Publication

Sedley W et al. Intracranial mapping of a cortical tinnitus system using residual inhibition. Current Biology, Published 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.075