A Glimpse Into Archaic Protein Synthesis Systems

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

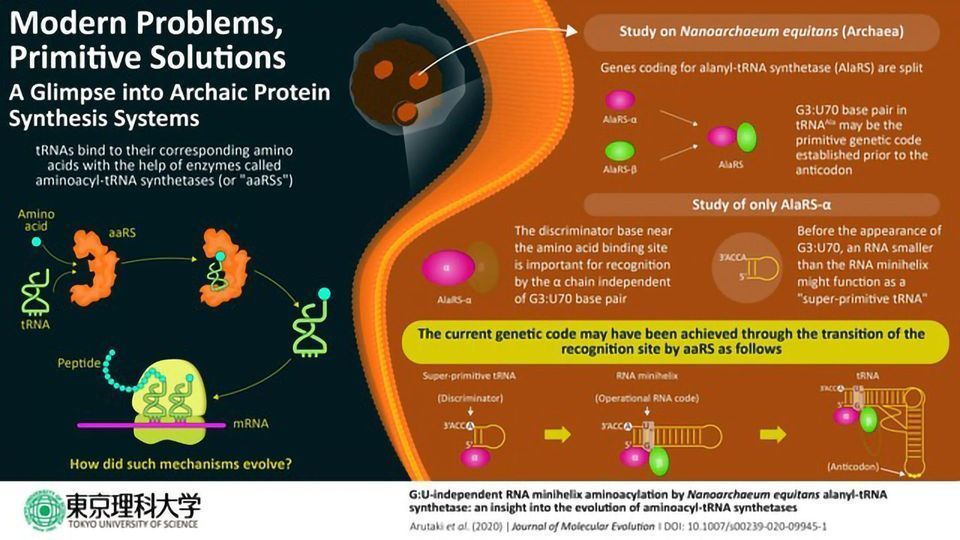

In cells, protein is synthesized based on the genetic code. Each protein is coded by the triplet combination of chemicals called "nucleotides," and a continuous "reading" of any set of triplet codes will, after a multi-step process, result in the creation of a chain of amino acids, a protein.

The genetic code is matched with the correct amino acid by a special functional RNA aptly named transfer RNA or tRNA (which, incidentally, is itself composed of its own type of "codes").

An enzyme called "aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase" or aaRS accurately assigns a specific amino acid to the correct "code" through a tRNA by recognizing unique structural components called 'identity elements' on the tRNA. In the case of the amino acid alanine, the identity element for recognition by the enzyme alanyl-tRNA synthetase (AlaRS) is an unlikely base pair "G3:U70," present in the minihelix structure (amino acid-accepting upper half region) of tRNA. Considering its importance in the recognition of the code, the base pair is popularly known as the "operational RNA code."

The evolution of this complex tRNA-aaRS system is a fascinating enigma, as the existing evolutionary evidence suggests that the upper half of the tRNA containing this operational code appeared earlier in evolutionary history than the lower half part that binds to the triplet code of mRNA. Interestingly, in a primitive microorganism, Nanoarchaeum equitans, the genes coding for each AlaRS subunit α and β are split, with the two genes being separated by half the length of the chromosome.

This interesting fact inspired a team of scientists at Tokyo University of Science, led by Prof. Koji Tamura, to hypothesize that these split forms of AlaRS in N. equitans might be connected with the evolutionary history of aaRS enzyme activity.

Prof. Tamura emphasizes the significance of their study, published in Journal of Molecular Evolution, in the evolutionary context, "AlaRS-α shows the G3:U70-independent addition of alanine to RNA minihelix regions. Our data indicate the existence of a simplified process of alanine addition to tRNA by AlaRS early in the evolutionary process, before the appearance of the G3:U70 base pair."

The aforementioned minihelix parts of tRNAs were previously known to function as the region of occurrence of addition of amino acids by many aaRSs. To understand the interaction process of the minihelix (minihelixAla) of alanine-specific tRNA (tRNAAla) and AlaRS subunits, the researchers cloned the coding sequences of α and β subunits of N. equitans and then purified the synthesized proteins.

The researchers noticed that, at a relatively high concentration, AlaRS-α alone was capable of adding alanine to both tRNAAla and minihelixAla. Then also observed that AlaRS-α alone interacts with the end of the alanine-accepting region of tRNAAla, but not with the G3:U70 base pair. This was in stark contrast to prior knowledge regarding tRNAAla and AlaRS system. In brief, when both AlaRS-α and AlaRS-β were present, AlaRS behaved in a G3:U70-dependent manner, but working alone, AlaRS-α could add alanine to tRNAAla and minihelixAla in a G3:U70-independent manner. The researchers deduced that "the G3:U70 may be a late-arriving 'operational RNA code,' relevant to later alanylation systems incorporating further specificity through the evolution of the AlaRS-β subunit."

So, what makes the findings of this study so important? Prof. Tamura explains the significance of the striking results of their research, "our findings reveal for the first time that a G3:U70-independent mechanism of alanine addition exists. Furthermore, using 'RNA minihelix' molecules, which are considered to be the primitive form of tRNA, we could also illuminate the 'morphology' of tRNA before the evolutionary appearance of the G3:U70 base pair.''

While discussing the broader implication of their study, Prof. Tamura comments thoughtfully "The breakthroughs in science almost always came from the curiosity-driven research, and the results of our study approach the mystery of the origin of life. It has the potential to transform many areas". His team is now focusing on an extensive structural analysis using the mutants of N. equitans AlaRS-α, but their current findings, published in August issue in printing and selected as the cover of the August issue, are enough to give cause to rethink chapters scientists that have believed to be fundamental in evolutionary history!

Reference: Arutaki et al. (2020). G:U-Independent RNA Minihelix Aminoacylation by Nanoarchaeum equitans Alanyl-tRNA Synthetase: An Insight into the Evolution of Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases. Journal of Molecular Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00239-020-09945-1.

This article has been republished from the following materials. Note: material may have been edited for length and content. For further information, please contact the cited source.