Refugee Returns to Raise Profile of Science in Kosovo

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

“Right now there is no neuroscience being taught in Kosovo”

Egzona Morina, a Ph.D student at University College London’s Sainsbury Wellcome Centre tells me over the telephone.

“I think there is a neurology department and there used to be a clinical psychology department in Pristina [the nation’s capital] but there is no formal teaching of neuroscience in the country.”

Egzona, herself a refugee of the conflict in Kosovo in the late 90’s, grew up in Belgium before gaining a tennis scholarship in the United States, where she then spent the formative years of her education.

“Right now there is no neuroscience being taught in Kosovo” -Egzona Morina, Neuroscience Ph.D Student and founder of BrainCamp KosovoWorking with children with dyslexia during her degree in clinical psychology took her away from the tennis court and made her want to pursue a master’s degree in neuroscience and education at Columbia University. A psychopathology class caught her interest and she next moved from the classroom to the lab, to work as a lab manager and technician at New York University (NYU) for several years.

She moved to London, UK, in 2017 to start a Ph.D studentship at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre for Neural Circuits and Behaviour following a summer in Kosovo where discussions with friends and family highlighted a gap in both the education of science and the pursuit of science careers by students in the country.

Map of Kosovo. A landlocked country in Southeastern Europe, Kosovo is bordered by Macedonia, Albania, Montenegro and Serbia. It has a population of 1.9 million. Its capital city is Pristina.

Map of Kosovo. A landlocked country in Southeastern Europe, Kosovo is bordered by Macedonia, Albania, Montenegro and Serbia. It has a population of 1.9 million. Its capital city is Pristina. Inspiring Young Minds in Kosovo

Newborn Monument, Pristina. The monument was unveiled on 17 February 2008, the day that Kosovo declared its independence from Serbia. The monument is painted differently every year, on the anniversary.

Newborn Monument, Pristina. The monument was unveiled on 17 February 2008, the day that Kosovo declared its independence from Serbia. The monument is painted differently every year, on the anniversary.Despite the highest economic growth among Western Balkan countries in 2017, Kosovo remains the third poorest country in Europe with a high rate of unemployment. The country gained its independence ten years ago (2008) yet is still not acknowledged by all members of the United Nations, nor all the members of the European Union, making migration difficult for its citizens. Coupled with the low employment rate, future prospects for Kosovo’s youth look bleak. Which could explain why young people are choosing to study for careers in finance, law and politics – careers they feel will make them globally more employable – instead of science.

Egzona felt strongly that by ignoring science they were missing a trick:

Backing BrainCamp Kosovo

She then sourced funding by pitching the idea of the camp to the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre’s leadership team. As Chief Scientific Officer Prof. Tom Otis explains:

“Egzona felt passionately that significant impact could be made from science education efforts like this. She made the case that by opening horizons for the best students in Kosovo we could change the trajectory of talented students at a key stage of their lives. The proposal and its promise was compelling.”

The Neuro-Syllabus

The students were enthusiastic and have a lot of potential, making it very inspiring to work with them. I hope to see some of them in the field in the future!” -Jesse Geerts, Neuroscience Ph.D Student and teacher at BrainCamp KosovoThe week began with a discussion about what exactly is ‘neuroscience’? – An umbrella term for the investigation of brain function – and how it needs a multidisciplinary, multi-angled research approach. It’s a field where scientists with backgrounds as diverse as chemistry, computer science and engineering, to physics and psychology, all approach the problem of understanding the brain in health and disease.

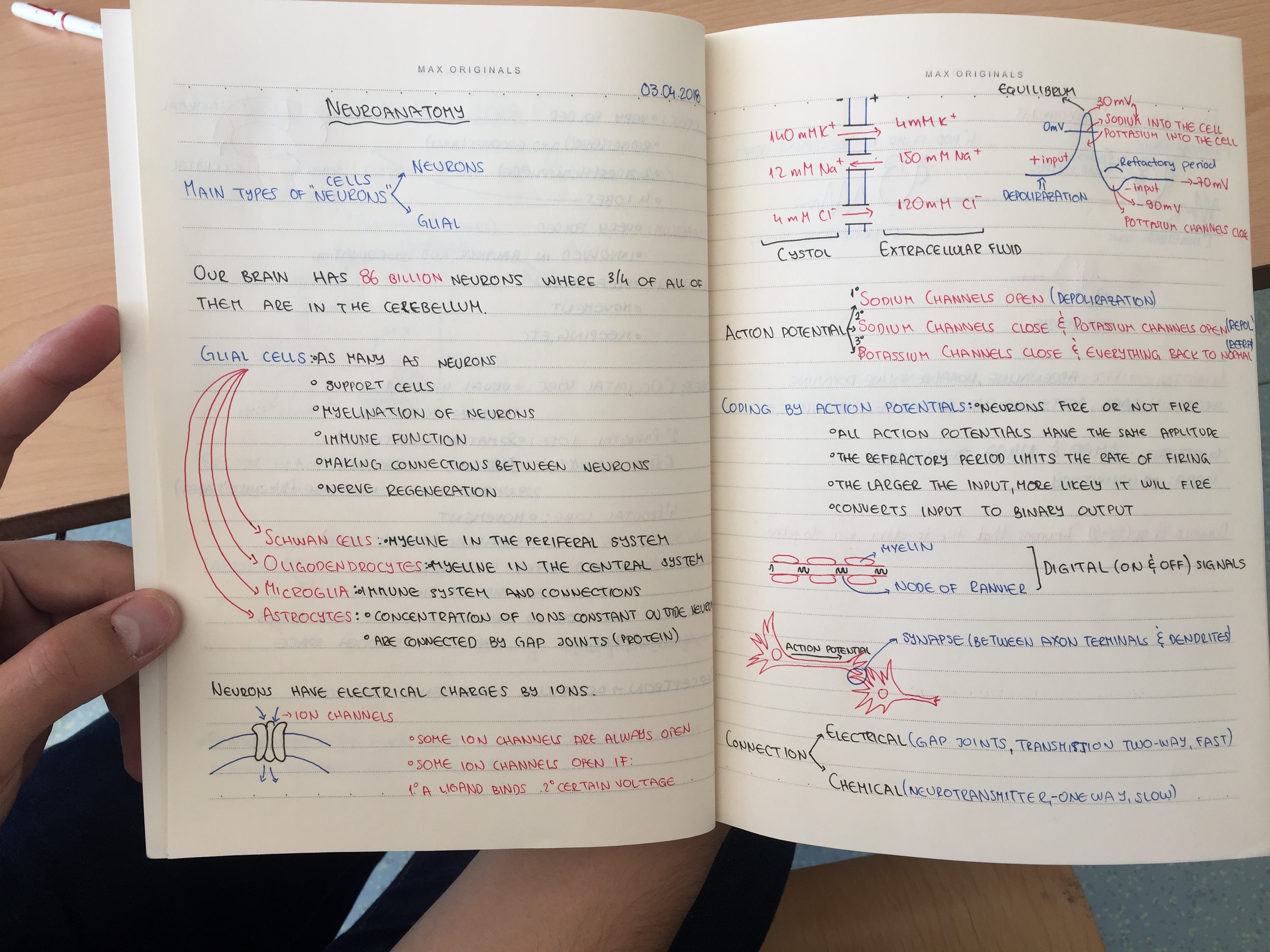

Next up was neuroanatomy. The group explored the different areas of the brain and their function, down to the different cell types of the brain, their cellular compartments and how they communicate with one another.

As the week progressed, they discussed how our brains make sense of our environment and enable us to respond in kind, such as running away from a threat.

“Teaching at BrainCamp Kosovo was a great experience. The students were enthusiastic and have a lot of potential, making it very inspiring to work with them. I hope to see some of them in the field in the future!”

The teachers also wanted to impart on the students how to think like scientists, how to develop a research question and consider how they would set about solving it.

This culminated in the end-of-course task in which the teachers challenged the students to present a research plan for how they would investigate a relevant neuroscience problem. The results of this task far exceeded the expectations of the teachers.

As Simon Thompson, a teacher on the course reflects:

“BrainCamp was an overwhelmingly excellent experience for everyone involved and highlighted the fact that when inquisitive minds meet intriguing ideas, brilliance will blossom; regardless of the borders and cultural differences that can exist.”

Recognizing Potential: The future of neuroscience in Kosovo

“I don’t want this to just be a week every year where we go and teach neuroscience to students in Kosovo and then come back to our lives in London, leaving them to go back to theirs in Kosovo.”

“Having seen how quickly these kids grasped and explored the complex subject matter, I’m committed to getting neuroscience to feature on the curriculum in Kosovo.”

This view was echoed by Prof. Tom Otis when asked if the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre would support the camp next year:

“Yes, I think we will support another version. As for future plans, Egzona has been thinking about both the sustainability and opportunities for growth for BrainCamp Kosovo. We will definitely be reaching out to potential partners.”

Adding: “We also hope to involve those positively impacted by the program as we go forward.”

And why not? Given what they achieved in just five days, it’s tempting to imagine what these students could achieve in a year’s worth of neuroscience teaching. By making BrainCamp Kosovo self-sustaining, Egzona will be able to perpetuate neuroscience teaching in the country, and perhaps enable some of these students to continue their education in neuroscience in some of the bigger centers around the world, just like she was able to do at Columbia, NYU and now the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre for Neural Circuits and Behaviour, UCL.

By capturing the imagination of students with science at an early age, who knows what they could achieve. As Prof. Tom Otis concludes:

“It is incredibly powerful to engage students at an early career stage with material that educates them about the best science and also inspires them. Once a young potential scholar is hooked, they can be set on a path to change the world!”